by Jari Villanueva

©2021 Jari Villanueva TapsBugler.com

Among the 137 marches composed by John Philip Sousa (1854-1932) can be found some of the most stirring music ever written by an American composer. Sousa defined the “American” march form with its distinctive sound and construction. His output of marches began in 1873 with his composition “Review” and ended with his “Library of Congress” written, but left unfinished, shortly before his death. Sousa’s music epitomized the American spirit and his marches are played around the world by school and university ensembles, community bands, symphony orchestras, brass bands, military organizations and all types of musical groups.

Much has been written about the marches. They have been studied, analyzed, edited, arranged into various configurations, and recorded countless times. At the time of this writing, the United States Marine Band is near the end of a multi-year project of recording the first comprehensive collection of Sousa’s marches since the 1970s. The recordings will be in chronological order and available for free download on the US Marine Band website, along with scrolling videos and PDFs of the full scores that include historical and editorial notes about each selection.

Throughout the past decades, editions of Sousa marches have been edited and published by Dr. Fredrick Fennell, (conductor of the Eastman Wind Ensemble), Mr. Loras Schissel (Sousa scholar and Library of Congress Music Supervisor), Mr. Keith Brion (Sousa scholar, Sousa impersonator and conductor of the New Sousa Band), Colonel (ret) John R. Bourgeois (former Director of the US Marine Band), and others. Much of the editions deal with performance practices and correction of notes and articulations. These editions have helped improve the quality of performances for bands.

An overlooked facet of these marches is the use of bugle marches and bugle calls incorporated into approximately 20 compositions. We listen to two of his most famous marches “Semper Fidelis” and “The Thunderer” (both written a year apart while Sousa served as the Leader (Director) of the US Marine Band) and are familiar with the sections that use a bugle march as a strain. These are but two selections that employ a bugle march (in these two cases marches taken from his 1886 manual “Instruction for the Field-Trumpet and Drum”) and enhance the compositions greatly with their military flourish.

Bugle marches were very common in field music from about 1880 to the 1950s before they started to evolve into the DCI (Drum Corps International) type of Drums and Bugle Corps format we have today. Sousa knew of this form of music with his time in the US Marine Band and later as the director of the Navy Bands at Great Lakes Training Center during World War I.

This article will look at those marches that use bugle signals and bugle marches. It will also look at the derivation of the marches and any actual bugle calls placed into a march. We will also look at the field music publications and other works that incorporate bugle signals. Another aspect considered is the particular instrument Sousa had in mind when he wrote these bugle marches.

It is important to note that the author uses the terms “bugle” and “trumpet” (or “field trumpet”) throughout. Both terms refer to valveless brass instruments. The basic difference comes from the shape of the instrument with regard to the bell. Bugles have more of a conical shape while the trumpet (or field trumpet) has a more cylindrical flare resulting in a brighter, brassier sound than a bugle. While it is easy to classify the trumpets as cavalry signal horns and bugles as infantry instruments, this was not always the case.

During Sousa’s lifetime the military bugle and trumpet in the United States went through various configurations and keys. Changes were made by the military in 1865, 1879, 1892, and 1894. These specifications included the redesign of the military signal horn in both shape and key. Not only would Sousa have to have known what instrument was being used widely but also be able to incorporate it into his compositions.

In order to understand this we must first look at what bugle and trumpet signals were being used before his time and how bugle marches came into being.

Since Biblical times, bugles and trumpets were used as an effective way to communicate over long distances. Hence, it was natural that they were adopted for military use. Historical records tell of great battles heralded by trumpet blasts. During the time of the Napoleonic Wars, these signals or calls were written down in the infantry manuals of the day. As the American military came into existence, English, then French bugle calls were borrowed for use in the United States infantry, cavalry and artillery.

The importance of signal instruments in the US military was evidenced by the adoption of the trumpet as a symbol for mounted rifles in the early 19th century, and of the bugle as a symbol for infantry during the Civil War.

Early American use of horn signaling paralleled that of the British Army. Shortly before the outbreak of armed rebellion in the North American colonies, the British Army had introduced trumpet signals for dragoons and the Halbmond or Hanoverian horn calls for light infantry. Raoul Camus in his thesis “The Military Band in the United States Army Prior to 1834” suggests that American militia and some elements of the Continental Army incorporated these British horn signals into their field music.

For more information on early use of bugles in the U.S. military:

“The Evolution of Trumpet and Bugle Signals in the United States Military from 1798-1874”

www.tapsbugler.com/bugles-and-bugling-prior-to-the-civil-war/

After the Revolution, during the 1790s when the US Army briefly assumed its unique legion structure, Congress authorized one “trumpeter” in each of the four company-size units of the legion’s dragoon squadrons. In the cavalry volume of an unofficial military treatise published in 1798, American compiler E. Hoyt listed and described trumpet calls, including “Boots and Saddles.” Hoyt’s 1811 “Practical Instructions for Military Officers” covers trumpets (“Each troop of cavalry has one”) and “Bugle-horns” (“now used by the light infantry and rifle corps…also used by the horse artillery and some regiments of cavalry”). Another compiler of military information, William Duane in his 1809 compendium, proposed a standard system of signals for the army’s field instruments and adapted his music to the bugle.

The British published bugle music before the Americans. John Hyde’s “A New and Compleat Preceptor for the Trumpet and Bugle Horn” was published in 1799 with a second edition in 1800. This music contains three sections:

1) Music for trumpets for use in the Cavalry with appropriate calls for Stable, Boots and Saddles, To Horse, and Water Call.

2) Music for Bugle Horn for use in the Light Infantry with signals for skirmisher calls and duty calls for camp or garrison.

3) Duets for Bugle Horns by F. Fraser.

Groups of buglers were used to sound the calls and play marches written for two, three, and four parts. This is the first known use of bugle bands or corps, a forerunner of the drum and bugle corps of today. In 1804 James Gilbert, a musician with light dragoons, militia and cavalry regiments, wrote a manual of calls for riflemen and light infantry that included the infantry calls for the bugle and thirty-six marches and quicksteps. These thirty-six pieces are written for three parts but include no drum part.

What exactly makes up a “Bugle March?” Bugle marches are defined for our purposes as compositions that are written in two eight-bar phrases. These are in 2/4, 4/4 or 6/8 time and can be fitted to the standard drum cadences of the period commonly called “Army 2/4” or “Army 6/8.” These drum cadences are standard as they are same used by fifers as accompaniment to hundreds of tunes.

There were few marches included in the early US military manuals and the idea of bugle corps or bands probably did not occur until the Civil War. Field Music (the military musical groups consisting of fifes, drums and bugles) developed prior to the Civil War. There was however music for fife and drum as early as 1819. The first bugle calls to be considered as marches are found in the 1835 “Infantry Tactics” manual by Winfield Scott. They are: No. 4 Common Time, No. 5 Quick Time, and No. 6 The Reveille.

Bugle marches could be found in the manuals of the Civil War period. The infantry still used the three listed above. In the cavalry manual calls written in the march form appeared. In the 1862 Cavalry Tactics we find: No. 6 To the Standard, No. 23 Common Step and a Quick March in 6/8 time.

Here are some Bugle Marches of the Civil War performed on original Civil War bugles and drums

There are accounts of bugle corps being formed in regiments that had buglers within their companies. These corps were led by the Chief Bugler of the regiment who held the same position and responsibilities as a Principal Musician. Oliver Willcox Norton of the 83rd Pennsylvania Volunteers wrote home in a letter dated April 8, 1863, “The Colonel’s reason for promoting me was to put me in charge of the bugle corps here to play for dress parade in the place of a band.” The music performed by the bugle corps must have been limited as few publications printed music for bugle marches. One source for marches was the “Army Regulations for Drum, Fife and Bugle” by William Nevins, arranged by A. J. Vass published in 1861. There are ten selections called Quicksteps that fit the bugle march form. Although not stated, they work well with drums.

Following the war publications were printed with bugle marches included. A notable one was “The Trumpeter’s Call Book” by Ellis Pugh, a former bugler during the war and Trumpeter of the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry.

The United States Army discontinued its use of the fife for signaling and adopted the bugle around 1874. The bugle, as proven during the Civil War, was more effective than the human voice at transmitting commands along the long lines of troops and easier to hear over long distances. That year a new infantry manual was published by Major General Emory Upton. This manual included a complete revision of bugle signals. Under the supervision of Major General Truman Seymour, just about all the Civil War infantry calls, which had been borrowed from the French, were removed and replaced with signals from the cavalry and artillery manuals. In addition new calls appeared for the first time including new versions of “To the Color,” “Adjutant’s Call,” “Generals March,” and a “Flourish for Review” (Ruffles and Flourishes). Also included were five Quicksteps (bugle marches).

On July 1, 1881 the United States Marine Corps officially replaced the fife with the bugle. The Marine fifers were not happy with this and the situation turned worse when a school was established at the Marine Barracks in Washington, D. C. for the purpose of training them to play bugles. Protests occurred, but the fifers were informed that they would not be allowed to re-enlist unless they agreed, in writing, to learn to “blow the bugle.”

It is interesting to note that despite this, fife music remained part of Army music manuals and Quartermaster’s catalogs listed the availability of fifes up to and through World War II. Also, fife instruction and tunes can be found in the US Marine Corps Manual For Field Music of 1935. So despite the fact that they were not used as signaling instruments, fifes never quite disappeared from military service. They are used today in units such as the Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps and have made a comeback with the Hellcats of the United States Military Academy.

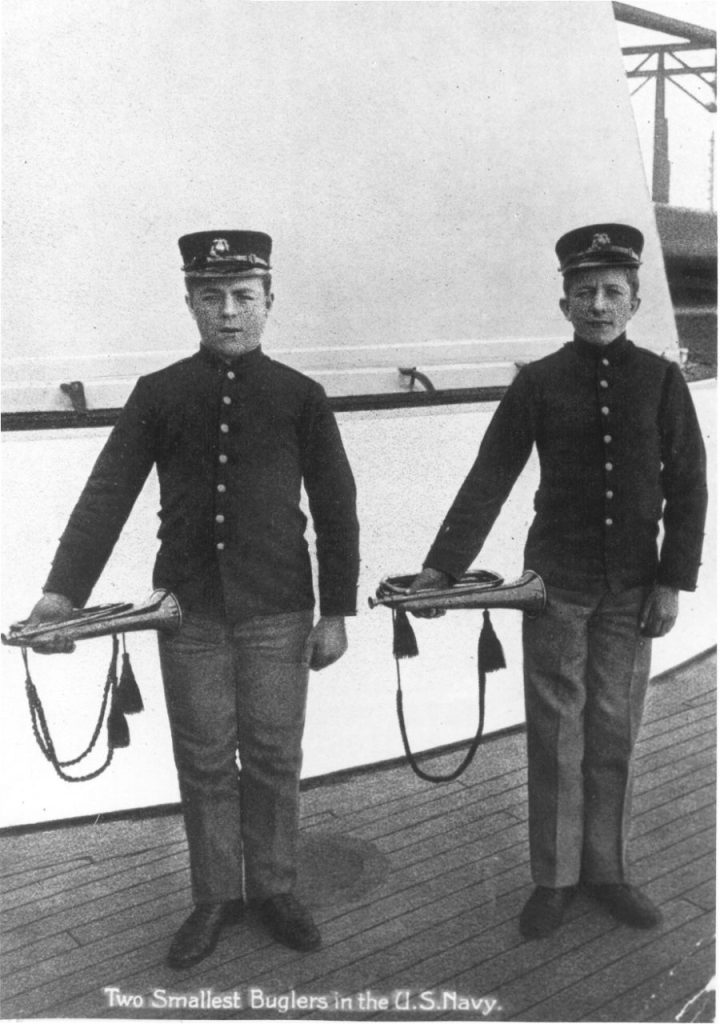

During the latter part of the nineteenth century, bugles of several varieties could be purchased from virtually every mail order musical instrument manufacturer. During the 1870s and 1880s, these bugles were paired with marching percussion throughout the country. The combination of the two became popular among the military forces. Often, these “trumpet and drum corps” would parade behind regimental brass bands during parades to play alternately during the march.

John Philip Sousa

Enter John Philip Sousa, America’s “March-King,” who by 1880 had made a reputation for himself as a theater musician and an up-and-coming composer. On October 1, 1880 Sousa was appointed the 17th leader of the United States Marine Band. He was to remain leader of the Marine Band for 12 years before launching a career as conductor of his own very successful touring band.

Sousa, growing up in Washington DC during the Civil War, certainly heard not only the brass bands from the hundreds of regiments that trooped through the capital, but also the sounds of fifes, drums and bugles. The field music would have been in his ear especially as the Army of the Potomac paraded in review in May 1865 with field music and brass bands blaring. He served as an apprentice musician in the Marine Band from 1868-1875 and, as all other apprentices, became schooled in the field music instruments as part of his rudimental military music training.

The signals Sousa would have heard and learned were those of the infantry, cavalry and artillery. Each branch of service had their own specific signals. This accounted for an abundance of military signals as the infantry used about 50, the cavalry 35 and the artillery, 35 calls.

Sousa wrote “Four Marches for Regimental Drums and Trumpets” in 1884. These were published by Harry Coleman of Philadelphia and although it is not specified what instrument is to play these marches, they were probably meant to be performed on G or F trumpets. In response to the increasing popularity of the trumpet and drum corps in Washington, D.C., Sousa published a book in hopes of developing their precision. “A Book of Instruction for the Field-Trumpet and Drum” published in 1886 by Carl Fischer (a reprint was done by Ludwig Music) included basic music theory, technical exercises for the trumpet and percussion, standard bugle calls, and eight original compositions prepared expressly for the trumpet and drum corps.

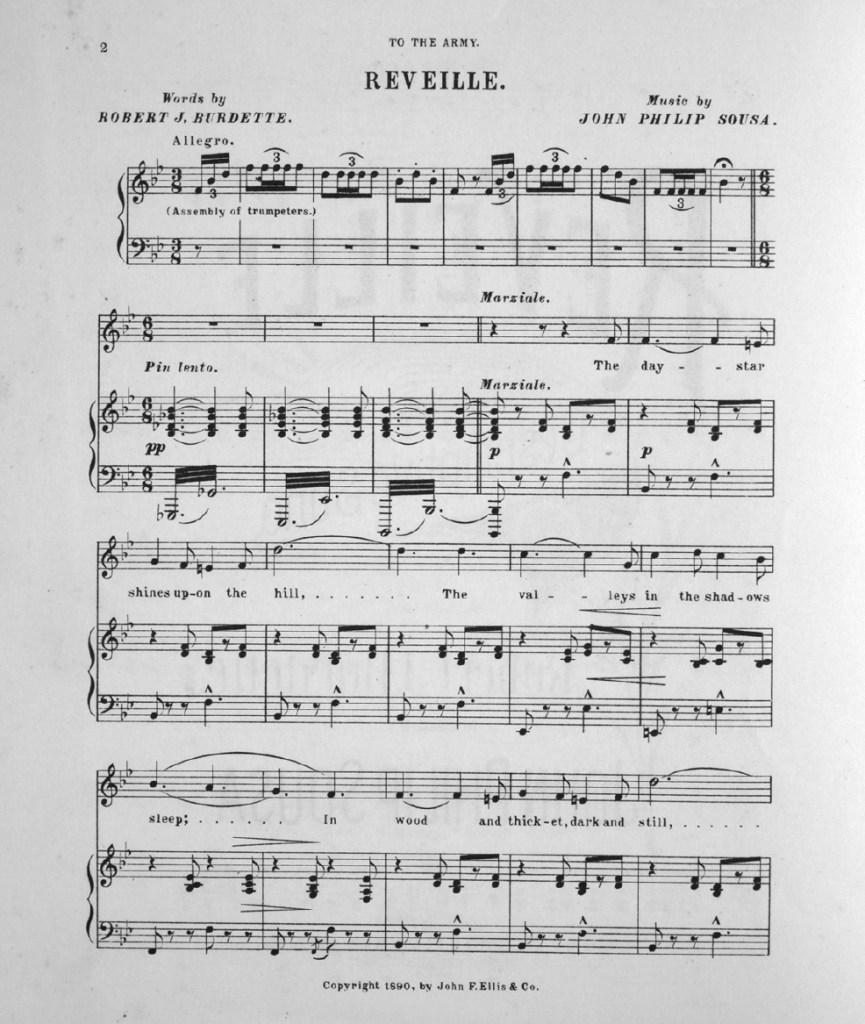

Sousa’s fondness for the bugle also manifested itself in his 1890 composition “Reveille Descriptive Song” with words by Robert J. Burdette. Published by John F. Ellis & Co. Washington, the song is a setting of Burdette’s poem from “The Drums of the 47th” and uses both Assembly of the Trumpeters and Reveille.

BUGLES IN THE LATTER PART OF THE 19TH CENTURY

Let us look at the bugles and field trumpets Sousa would have been familiar with during his lifetime. Sousa would have seen and heard many types of bugles, trumpets and other signal type horns but wrote calls in only two keys (F and B-flat ) in his marches. These were the two dominant keys for signal horns in the United States during the second half of the 19th century until the G trumpet was developed in 1892.

During the Civil War there was no official specifications issued by the Quartermaster Department other than the term “Bugles” and “Trumpets.” Quartermaster records of 1864 mention “brass trumpets” and “copper bugles.” Until 1879, the War Department specified signal horns per patterns on file or with only very bare descriptions. Various types of G trumpets with and without tuning slides saw use during the American Civil War. All of these G trumpets and the similar F trumpets were two-coil horns usually in brass sometimes fitted with a bell garland. (A garland is an extra plate of brass that is fitted on the bell of a bugle for reinforcement.) The Civil War signal horns consisted of C bugles with or with out B-flat crook, F trumpets and a few forms of G trumpets plus the officer’s bugle which was non-regulation.

The instrument in greatest use during the Civil War was the large belled bugle (clairon) imported from Europe and used mainly in the infantry. Clairons are approx. 14-½ inches in length without a crook and 17 inches with one. The bell measures 5-½ inches in diameter.

This was the most common type of bugle used during the American Civil War. This big-belled instrument is in the key of C but can be lowered to B-flat with the use of a crook (a pig-tailed piece of tubing). The bugle is a single twist instrument made of copper with a brass garland and a reinforcing band made of brass approximately eight inches up from the bell. There are examples of these horns in brass but for the most part they were copper. These “regulation” bugles were imported in large quantities during the 1860s or imported under contract, and stamped, by Stratton & Foote, Horstmann, Klemm Bros., Draper Bros., Church, and others.

In May1865 the Quartermaster for issued specs for G Trumpets and C Bugles

“Trumpets –

To be made of brass; when plain, viz; without crooks, to stand in F; with tuning slide and three crooks; to stand in G; they are to be 14-1/4 inches high…..with crooks, 5 or 5-1/4 inches wide in the middle and to weigh including crooks and without mouthpiece about 1 pound 2 ounces….the bowl (bell) about 5- or 5-1/4 inches in diameter….

Bugles to be made of copper and to stand in C…”

This seemed to be the standard for the military in the post-Civil War era. Certainly these signal instruments were used in the army and certainly taken out to the west as the military shifted its attention there following the four-year conflict. However, the large belled clairons were still used in the years following the Civil War as stocks of these horns (those that didn’t go home with their owners) still existed.

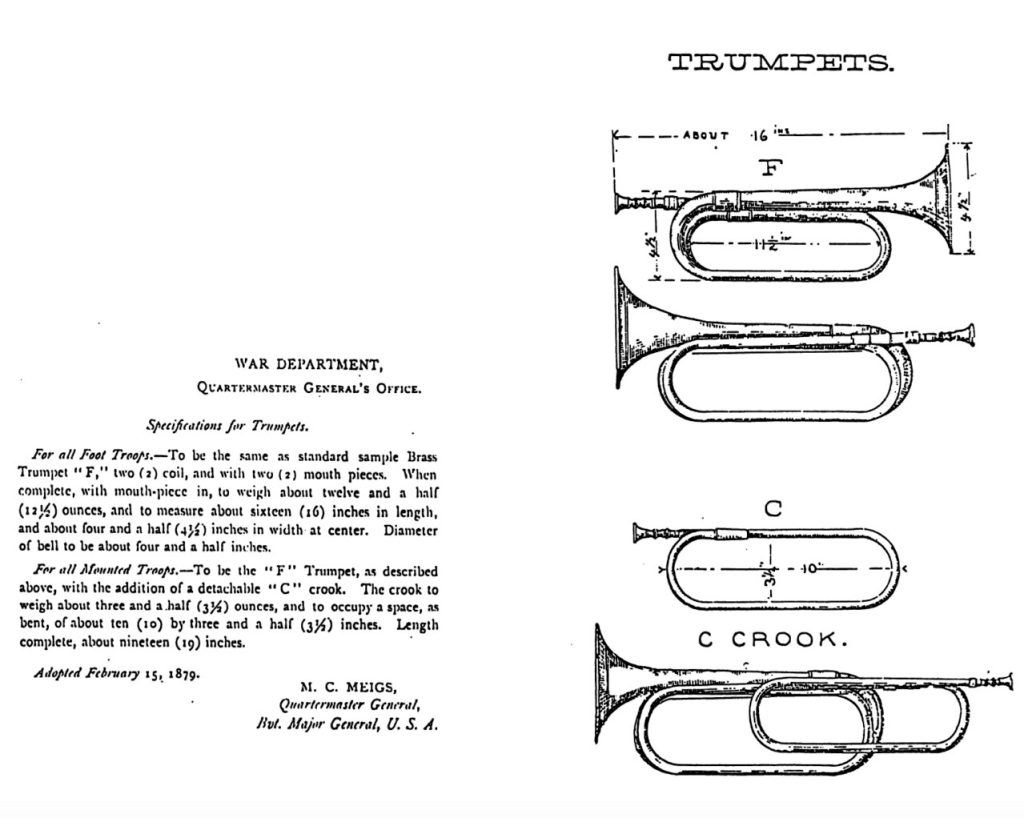

In 1879 came the next major design change for military signal instruments in the US Army. This is commonly known as the M1879 which was authorized by the Quartermaster General (Montgomery Megis) who published new specifications for Trumpets. These specifications were for both Infantry (Foot Troops) and Cavalry (Mounted Troops)

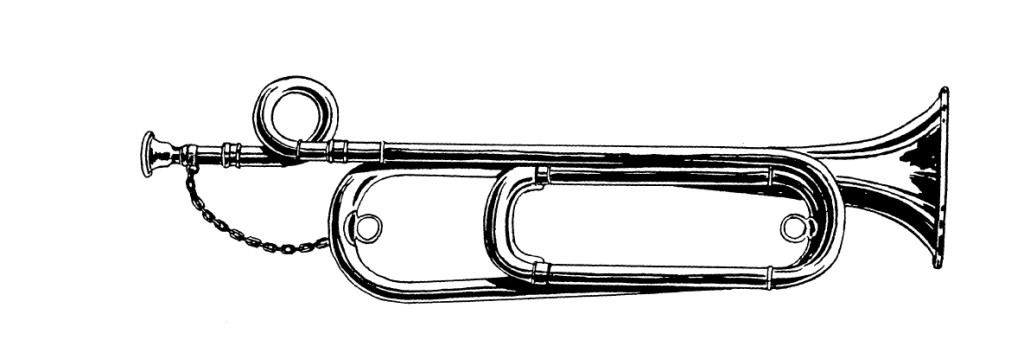

This was the introduction of the Trumpet in F with a detachable crook lowering the horn to the key of C. These double-coiled instruments are 16 inches in length with a 4-½ inch bell diameter. They are brass with a garland. American manufactures included Wurlitzer, Stratton, Klemm, Stratton and Foote.

This is the “Regimental Trumpet” Sousa was familiar with and the instrument for which he wrote his “Four Marches for Regimental Trumpets and Drums” in 1884 and his manual “A Book of Instruction for the Field-Trumpet and Drum” in 1886.

In 1892 came the most radical change in field trumpet/bugle design. This was the introduction of the M1892 Trumpet. This Trumpet which would forever be also referred to as a “bugle” would be the basic design for every signal instrument in the United States and the horn used, with variations and modifications, by drum and bugle corps for the next century. It would even be adopted by the Boy Scouts as their signal instrument.

This basic horn came into being as the standard U.S. Army Cavalry trumpet in G, specification No. 325 dated May 2, 1892 (Quartermaster General’s Office, War Department) which supplanted the previous model 1879 F Trumpet with C crook. These were characterized by detailed specifications with drawings and dimensions. Length 16-17 in., Bell diameter 4 ½ in.

Trumpets-To be made of what is known as special first class quality trumpet brass, twenty-three (23) gauge, strengthened at the outer edge of the bell by three-sixteenths (3/16) of an inch solid round brass wire: the stay of the tuning slide to be of solid half round three-sixteenths (3/16) of an inch brass wire, fitted to the inner side of the bow, and soldered to the ferrule with hard silver solder; the back stay to be of solid wire concave on either side, two (2) inches long: of three-sixteenths (716) of an inch brass wire. To Have two( 2) brass rings of number nine ( 9) wire with one-half ( 1/2) of an inch opening, secured to three-fourths ( 14) of an inch circular plates, soldered on for the trumpet cord, one at the inner portion of the top bend, and the other on the in’1er portion of the lower bend. The mouth ferrule to be of double thickness of tubing, about one and one-eighth (1 1/8) inches long, fitting exactly the taper of the mouth-pikece shank. The bell portion to be of the best hammered brass.

Each trumpet to have two (2) brass nickel-plated mouthpieces of separate and distinct sizes; the largest size to be attached to the trumpet by a six and one-half (6 1/2) inch nickel-plated chain.

Each trumpet to be built in the key of “G;” the slide to draw to “F,” and marked and stamped with the letter “F” at the correct point to produce the key of “F.” Each instrument must be made on the prototype system in order to insure a perfect equality of tone.

The trumpet, including chain and one mouth-piece. To weigh not less than seventeen and one-half( 17 1/2) ounces, the diameter of the bell to be four and three-eighths (4 3/8 ) inches; the extreme length to be about fifteen (15) inches, not including mouth-piece; extreme width to be about four (4) inches; the entire instrument to have a thorough brass-instrument polish.

“F” Crooks.-The metal to be the same as described for the trumpet; to be about nine and one-fourth (914) inches long formed into a single coil, one end projecting and reinforced with a ferrule one-half (1/2) of an inch deep, to receive to receive the mouthpiece; the other end properly tapered to fir the tubing of the trumpet, and adjusted thereto to produce the key of “F”

All to be like and equal to the standard samples.

The original specification called for a crook to lower the pitch of the horn from G to F but it was easier to pull the tuning slide out to a pre-marked location and the crook was later dropped.

There are no Sousa marches that uses the M1892 in its manufactured form. The key of G is not a favorable key for wind/brass bands. The marches written after 1892 use the M1892 with the added crook or slide pulled out to lower to the key of F.

Two years after the introduction of the M1892 Trumpet came the M1894 Bugle. This bugle in B-flat, also referred to as a “Trench” bugle was manufactured for the military under the specification #1152 dated April 25th, 1912 and those manufactured for use during World War I are identified by the writing on the bell which marks the manufacturer, specification number (Spec. 1152), and date of production. The military versions were issued with a leather carrying strap. They have no tuning slides and the pitch is not consistent between horns. Military issues prior to 1912 have been found without markings like those manufactured for civilian use, and can be distinguished from subsequent issues by the thinness of the tabard (cord) rings and a shiny brass finish.

Length 10 in., Bell diameter 3 ½ in.,

Leather Strap approx. 50 in.

The following are the Specifications for the manufacture of the B-flat Bugle as published by the Quartermaster Department of the Army.

To be made of what is known as “Special first-class quality trumpet brass’; twenty-three gauge, strengthened at the outer edge of bell by three-sixteenths of an inch solid, half-round brass wire. To have two brass rings of No.8 U.S. standard gauge wire, with one – half an inch opening-, secured to three-quarter inch circular plates soldered on for the sling strap, one at the inner portion of the top bend, and the other on the inner portion of the lower bend.

The mouth-ferrule to be of double thickness of tubing, about one inch long, fitting exactly the taper of the mouthpiece shank. To have a brass ferrule in center of each of the three back bends, about three-fourths of an inch long, fitting exactly the tubing of the bugle, to which it should be securely soldered. The bell portion to be of the best hammered brass. A loose attaching link to neck of mouthpiece formed of No. 13 German silver wire, outer portion of link twisted 90 degrees to form a “D” toward lip-piece; loose ends of wire forming this link to be brought together and silver soldered.

Each bugle and mouthpiece to weigh about eleven and three-fourths ounces. The diameter of the bell to be about three and five-eighths inches; the extreme length to be about eight inches, not including mouthpiece; extreme width to be about four inches.

Each bugle to be built in the key of B-flat and made on the prototype system in order to insure a perfect quality of tone

Finish: Entire outer surface of both bugle and mouthpiece to be finished by sand-blasting. Finish interior of bell portion to the depth of three inches, to be also sand-blasted. Entire surface to be finished by sand-blasting, to be lacquered with transparent lacquer.

Sling: The sling to be made in two parts from russet collar leather. It consists of a one half inch piece, fifteen inches long overall, trimmed with a loose one-half inch bridle buckle attached to free end by an attaching button and sliding loop. Second piece is one-half inch by forty-two and one-fourth inches overall, is tapered and has six tongue-holes punched one inch apart, beginning two and one-fourth inches from tapered end. Both pieces are attached to their respective metal loops on bugle by a three-eighths inch leather loop.

Strap: The mouthpiece strap to be made of same leather as sling, three-eighths inch wide, seven and three-fourths inches long-over all; trimmings with bar buckle at one end, with a three-eighths inch leather loop on reverse side. Opposite end is tapered and punched with three tongue-holes at one-fourth inch centers, commencing at one inch from tapered end, the strap to be attached by means of a leather loop and is then buckled through the attaching link on the mouthpiece. In all points not covered by these specifications to be like and equal to the standard sample in all respects.

For Part 2 of this article click on link:

BUGLE MARCHES AND CALLS IN THE MARCHES OF JOHN PHILIP SOUSA Part 2

[…] post BUGLE MARCHES AND CALLS IN THE MARCHES OF JOHN PHILIP SOUSA Part 1 appeared first on Taps Bugler: Jari […]