OLIVER WILLCOX NORTON AND SHERMAN NEW YORK

By Jari Villanueva

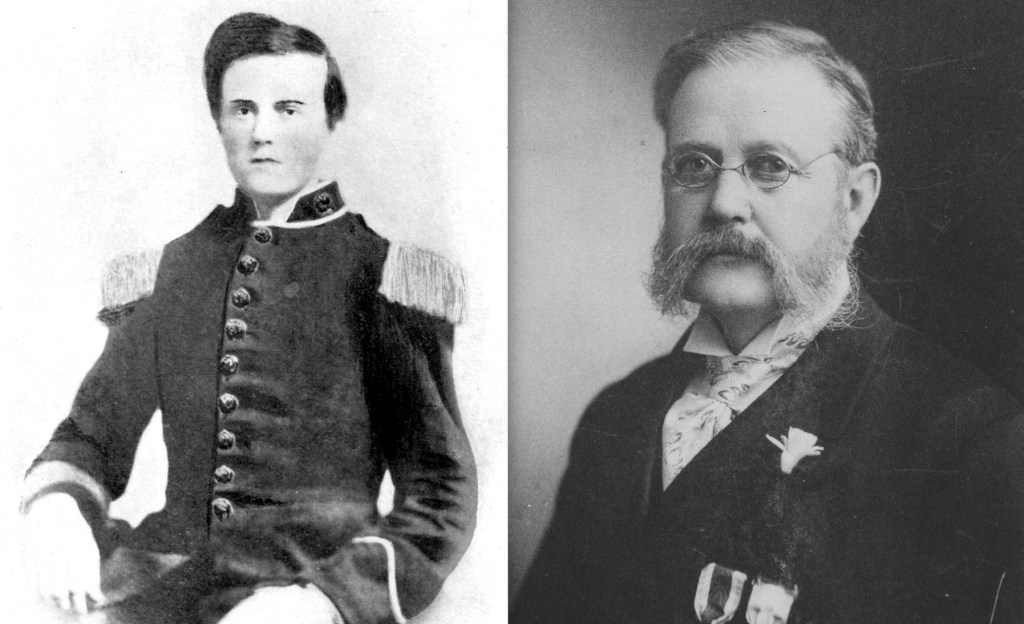

Oliver Willcox Norton (1839-1920) is best remembered as the first bugler to sound Taps. After the Civil War, he became a prominent businessman in Chicago. He never forgot the place where he was brought up and made significant contributions to the town of Sherman, New York.

Oliver Willcox Norton (O.W. to family and friends) was born in Angelica, New York (Allegheny County), on December 17, 1839. The son of Oliver William Norton, a Presbyterian minister, and his wife Henrietta, he was named after Henrietta’s father. Oliver was the oldest of thirteen children (the elder Norton had seven with his first wife Henrietta and six with his second wife, Sarah Swezey). Reverend Norton often relocated his family before the Civil War, and Oliver attended Montrose Academy in Montrose, Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania, and later attended a private school in Sherman, New York. The family then moved to Chautauqua County, New York, where Reverend Norton preached at Open Meadows Methodist Church near Sherman. In 1860, the family moved again to Springfield Township, Pennsylvania, where young Oliver was teaching and working on a farm when the Civil War broke out.

Oliver Norton is best known for serving as the brigade bugler for the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, 5th Corps. Under the command of General Daniel Adams Butterfield, he helped compose and sounded the bugle call of Taps for the first time at Harrison’s Landing (now Historic Berkeley Plantation) during the summer of 1862. He was the bugler when the brigade, led by Colonel Strong Vincent, fought at Gettysburg in July 1863 on Little Round Top. In November 1863, Oliver applied for and received a commission as an officer. He then spent the rest of the war with the 8th U.S. Colored Troops serving as a quartermaster officer.

After his discharge from the army in 1865, Oliver worked as a clerk at the Fourth National Bank in New York City. He lived in Brooklyn, near the ferry to Manhattan, where he met Lucy Coit Fanning. Lucy, born in Albion, New York, in 1842, attended Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn along with him. They married at the church on October 3, 1870, with Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, the well-known orator and antislavery preacher, officiating.

The over 150 letters Oliver wrote home during the war offer insight into his duties as a bugler, orderly, flag bearer, and his life as a soldier. They are collected in a book titled “Army Letters,” which he wrote in 1903 and published for private circulation. Nearly two-thirds of the wartime letters were written to his sister Elizabeth (Libby) Lane Norton

Elizabeth married Charles Ploss, a farmer, in 1862, and they had no children. Libby’s life remained based in Chautauqua County, but after Charles’s death in 1889, she left their farm home for a house in Sherman and later moved to the grounds of Chautauqua Institute, where her brothers Oliver and Edwin had built a comfortable home close to the community’s cultural attractions.

According to family legend, she was active in the Underground Railroad during the war, assisting runaway slaves in their escape to Canada. After the war, Libby became involved with the “Minerva Club,” a women’s social organization which worked to establish a free library in Sherman. She became blind later in life.

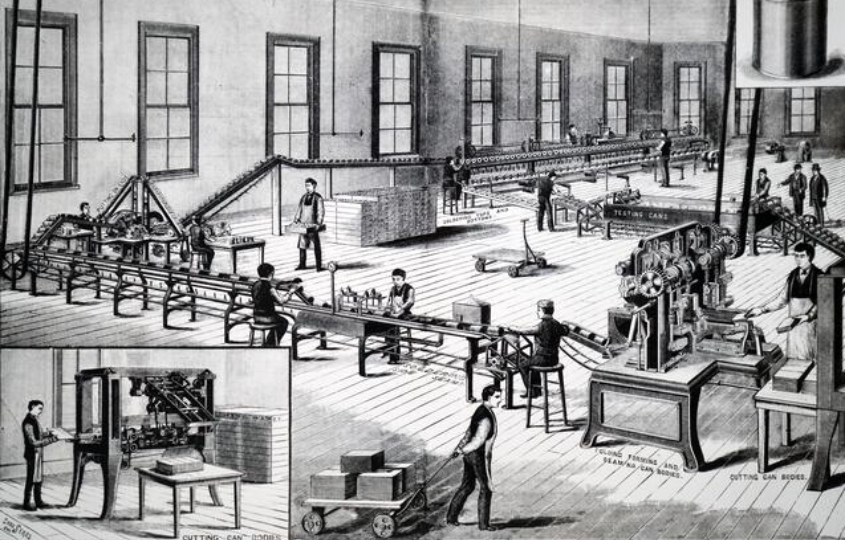

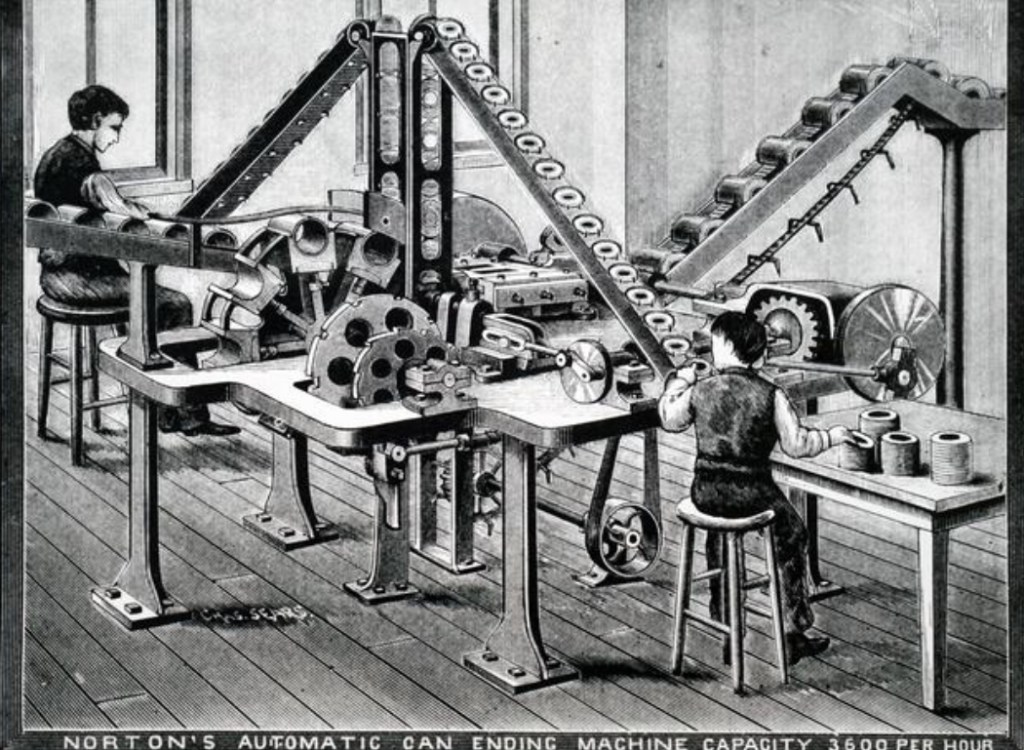

In 1868, Oliver’s younger brother, Edwin, operating under the name “E. Norton,” started his own tin can manufacturing business in Toledo, Ohio. At that time, tin plates were imported from Europe and made into cans in the United States. Edwin, who held over 5,000 patents, persuaded his older brother in 1873 to leave his accounting position in New York and form a partnership with him, Alton H. Fancher, and David Fanning. The company was called “Norton and Fancher,” and they manufactured cans and sheet metal goods.

Two years later, after Mr. Fancher’s retirement, the firm became the “Norton Brothers,” and they produced tea and coffee caddies along with other hand-decorated items for the Midwestern grocery trade. Over the following decade, the brothers patented several canning machines and became experts in Japanning, a tin decorating technique.

By 1880, the “Norton Brothers” plant in Chicago achieved a feat of mechanical efficiency that made 1883 a memorable year in the canning industry. The brothers created a fully automatic line for producing steel-bodied, tin-coated food containers at a relatively high speed of fifty cans per minute. This accomplishment, which replaced the slow-moving canners of the 1880s, was reported in the “American Machinist” and the “Scientific American” for August 1883.

By the turn of the century, over 100 tin can companies across America, including the “Norton Brothers,” merged to form the “American Can Company,” with Edwin Norton named as its first president.

Like his sister, Elizabeth, blindness overtook Oliver for the last 15 years of his life, and he was forced to withdraw from an active business role. However, he still kept himself occupied by writing three books based on his Civil War experiences: “Army Letters 1861-1865” (published privately in 1903 for his family members and friends), “Strong Vincent” in 1909, and “The Attack and Defense of Little Round Top” in 1913.

By an interesting coincidence, Oliver met a professor named George Vincent in Chicago, who was the son of Bishop John Vincent, co-founder of the Chautauqua Institute near Lake Chautauqua in western New York. Bishop Vincent and Colonel Strong Vincent (Norton’s old Civil War commander) were cousins.

Through this Chicago connection, Oliver and his family started visiting Chautauqua in the late 1800s and found it to be an ideal summer retreat from the city. Their vacation home was built by the lake at Chautauqua in 1901, and the family continued to spend summers there regularly, believing that the area was perfect for their young daughter Ruth, who used a wheelchair after a tragic fall from a cherry tree at age nine.

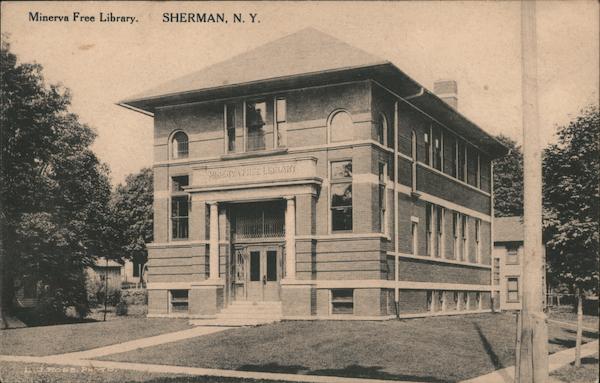

Sherman, New York, was familiar territory for Oliver because it was close to where he had spent part of his boyhood near his sister Elizabeth’s home. Oliver often visited Libby at her house in Sherman and became interested in the “Minerva Club,” which aimed to create a free library for the village. The humble start for this project was a dozen books kept in a market basket at the town hall, and Oliver saw this community spirit as worth encouraging, so he offered to help the group build a meeting place. Soon, plans for a public library were underway. Despite the blindness that shrouded his life from the turn of the century onward, he actively helped purchase the land near Libby’s home and contributed to the planning of the library.

Oliver donated $1,000 to buy the lot and $10,000 for construction, with the understanding that the town would cover taxes and maintenance. He wanted it to be the best-built, best-equipped library in western New York, and no detail was too small for his attention.

The Minerva Free Library opened to the public on February 13, 1909. In later years, Oliver continued to donate books and money to stock the new library, which by his death in 1920, held over 7,000 volumes. He also kept his interest in Sherman alive by sending donations of $500 toward a new school building. Between 1914 and 1915, he sent $15,000 for the improvement of the water works; in 1917, $15,000 for upgrading the town’s lighting system.

The Sherman band received $100, and $600 was sent for the final payment of the Soldiers’ Monument.

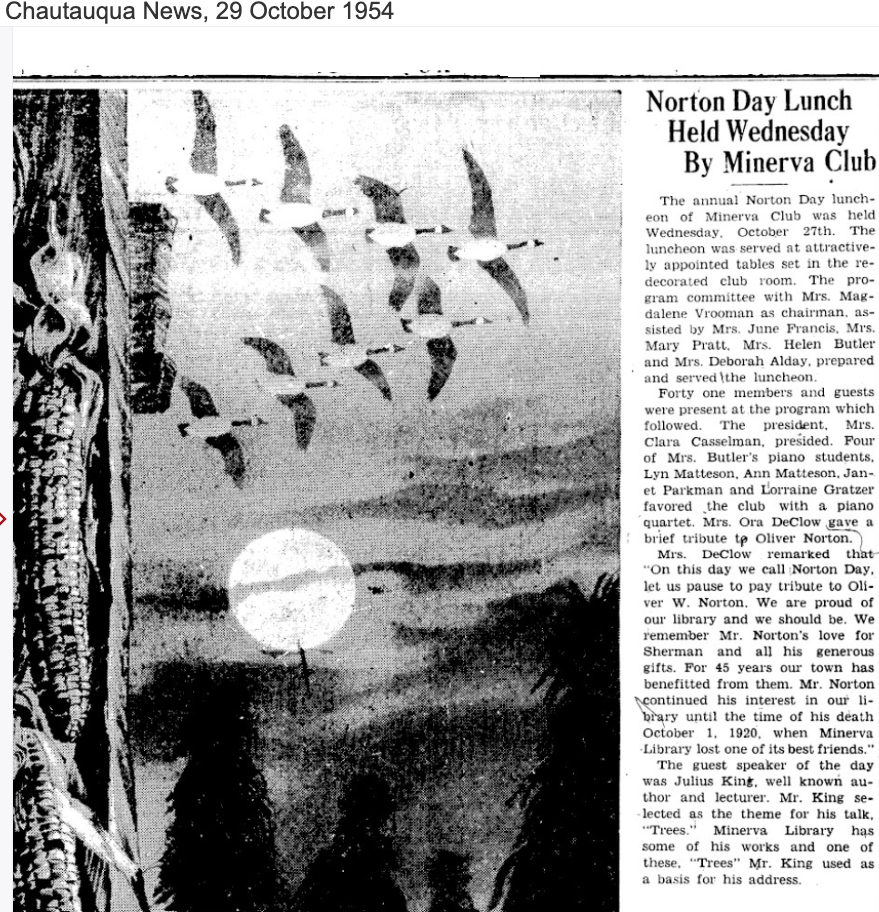

Although Oliver donated more than $75,000 to the town over the years, he preferred to keep his name out of the public record regarding the contributions. As a result, it took years before the townspeople knew for sure who was behind these generous gifts to their community. It is interesting to note that for many years after Oliver’s passing, the Minerva Club continued to honor Oliver annually as it met in the library he made possible. Records show that each year, the library paid tribute to Oliver Willcox Norton on October 1, the anniversary of his death, by lowering the US flag in front of the library to half-staff. He was also honored each year with an annual luncheon held to remember his contributions to Sherman, New York.